Bruce Davidson Digs Deep and Finds Gems He Had Overlooked

In the exhibition “The Way Back,” the photographer presents unseen outtakes from his nearly 70-year career as a chronicler of American life.

By Arthur Lubow, The New York Times, August 24, 2023

Breathtakingly fast and painstakingly slow: Before the introduction of the digital camera, a photographer worked in those parallel time frames. The click of the shutter was instantaneous, but then the film had to be developed, the contact sheets or color slides reviewed, and the selections made for printing.

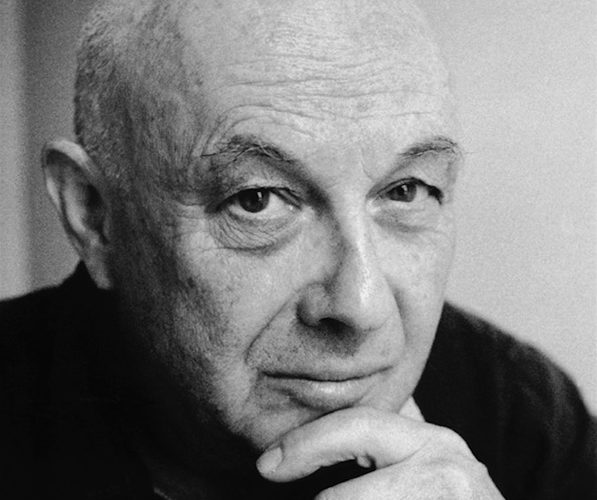

Pressed for time, a working photographer typically made these decisions hurriedly. In old age, there is time for reconsideration. Bruce Davidson, who turns 90 next month, has been reviewing his archive for the last eight years. In “The Way Back,” the title both of an exhibition now at the Howard Greenberg Gallery, in New York, and a more compendious book to be published this fall, he is presenting photos he overlooked, putting them on public view for the first time.

In a 2015 interview, Davidson named for me some photographers he thought had taken the art form to “a new departure point”: Eugène Atget, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Frank, Diane Arbus. He did not include himself. He knows he has followed trails blazed by pioneers. What makes him remarkable is the empathy that won over his subjects and the devoted persistence of his investigations.

Frank, who is probably Davidson’s greatest influence, restlessly sought to portray scenes and people new to him; it is one reason he did not enjoy or succeed at the lucrative task of crafting photo essays for Life magazine. In contrast, Davidson has preferred to mine the same subject for months or years, getting so close to people that you come to feel you know them yourself.

“I’m an Outsider on the Inside” An Interview with Bruce Davidson

Chris Wiley, The New Yorker, June 13, 2019

The photographer Bruce Davidson, who is eighty-five years old, has lived with his wife, Emily, in a rambling apartment on the Upper West Side for the past five decades. It is appointed with broken-in chairs and couches, an impressive folk-art collection, and has an extra bedroom, to accommodate visits from their four grandchildren. A bathroom has been transformed into a darkroom, complete with a custom-made Leitz enlarger and a fibre print washer installed in the claw-foot tub. An archive of Davidson’s prints and negatives are housed throughout the apartment in floor-to-ceiling shelving.

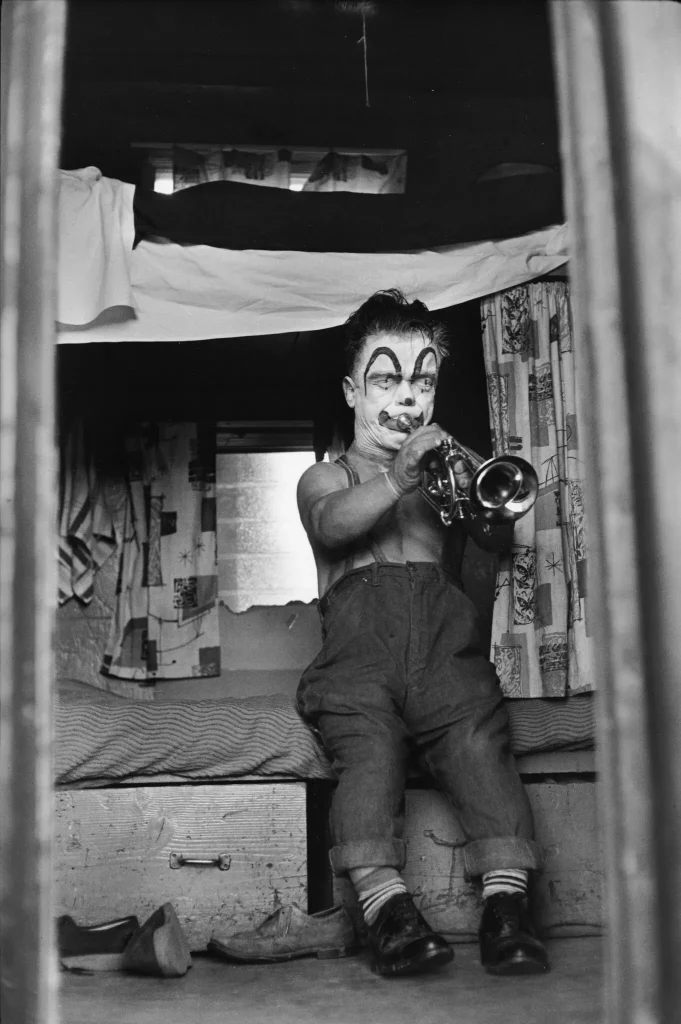

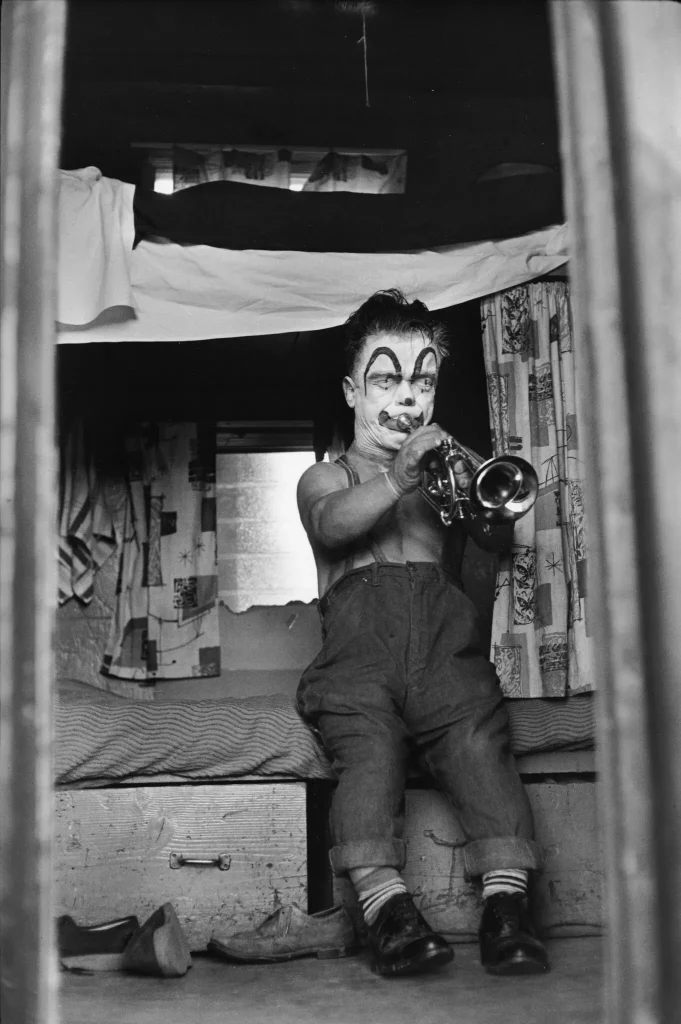

On a recent day, over tea and pistachio cake, Davidson sat down with me to reflect on his long and remarkable career, which is the subject of an exhibition on view through the end of this week at Howard Greenberg Gallery, in Manhattan. For more than six decades, Davidson has specialized in photographing people at society’s fringes: the lonely widow of a minor impressionist painter in Paris; a troupe of travelling circus performers; a teen-age gang in Brooklyn; the residents of a blighted block in East Harlem. Born in Illinois, Davidson grew up in Oak Park, outside of Chicago, and became interested in photography as a boy. He joined the Magnum photo agency in 1958. In 1961, having read about the attacks on the first Freedom Rider buses, he travelled south and joined the civil-rights protesters on the ride from Montgomery, Alabama, to Jackson, Mississippi.

“I’m a photographer. I take pictures.”

Davidson’s civil-rights work, which he pursued for five years, produced some of the most hopeful photographs of the Selma-to-Montgomery marches, as well as an indelible record of the violent repression that the civil-rights protests faced. It also marked Davidson’s political awakening as a photographer. In the late nineteen-sixties, he worked with the Metro North Association, an activist organization, to earn the trust of the East Harlem community he documented in his “East 100th Street” series. The Association later used Davidson’s images to advocate for neighborhood-revitalization projects. At one point in our conversation, I asked Davidson if he considered his own work to be a kind of activism, in the same lineage of an artist like Ben Shahn, who advocated for workers’ rights through his murals before signing up to photograph impoverished farmers as a part of the Depression-era Resettlement Administration (later the Farm Security Administration), or Davidson’s contemporary Danny Lyon, who photographed the civil-rights movement as a part of his involvement with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. But Davidson insists that he is less an activist or an intellectual than an observer, pure and simple. His desire is to see; his methods are instinctive. He told me, “I’m a photographer. I take pictures.”

“I am better seeing on the dark side of things than I am on the light. “

International Photography Hall of Fame: The photography of Bruce Davidson sheds light on subjects that have been isolated or marginalized from society and, in many cases, are hostile to outsiders themselves. His photographs show a keen desire to reveal and understand the complexities of individual lives and reflect universal truths and concerns.

Bruce Davidson was born in Oak Park, Illinois in 1933. He became interested in photography at age ten when his mother built him a darkroom in the family basement. After studying photography at the Rochester Institute of Technology and Yale University, he served as a military photographer stationed at the Supreme Headquarters of the Allied Powers in Europe. When he returned, his photographs were published in Life Magazine before he joined the prestigious photography agency, Magnum Photos.

Davidson’s early work was an important part of the photographic genre termed ‘the social landscape’ by photographer and curator Nathan Lyons in his exhibition and book entitled Contemporary Photographers Toward a Social Landscape (1966). This type of photography allows for the photographer to have a subjective point of view while working within a documentary tradition. Davidson often photographed groups or individuals isolated from society; his series on a teenage Brooklyn gang and another about a dwarf clown have become classics. His images are characterized by sensitivity, mutual trust and understanding.

Upon the completion of a series of photographs documenting the civil rights movement, he received the first photography grant ever awarded by the National Endowment for the Arts (1967). He spent the next two years photographing one city block in East Harlem. The resulting book and exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, East 100th Street, is a seminal and widely-referenced work, considered the first wed documentary and fine art photography.

Davidson’s photographs have appeared in numerous publications and his prints have been acquired by many museums worldwide. He has also directed three films.

Bruce Davidson: ‘Time of Change: Civil Rights Photographs, 1961-1965’

By Ken Johnson, The New York Times, August 15, 2013

In 1961 the photographer Bruce Davidson boarded a bus with a group of anti-segregationist Freedom Riders traveling from Montgomery, Ala., to Jackson, Miss. Two years later he was in Washington for the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech. In 1965 he joined the historic five-day march from Selma to Montgomery. Photographs from those and other excursions to the South as well as from Mr. Davidson’s hometown New York were gathered together in the book “Time of Change: Civil Rights Photographs, 1961-1965,”published in 2002. This poignant exhibition presents 37 of them.

The photographs avoid partisan sensationalism. There are images of watchful National Guard soldiers among ordinary people, both black and white, made during the 1961 bus trip. One shows a group of white men heckling the Freedom Riders. Walker Evans-like pictures show people living in extreme poverty in sharecropper cabins. But few document instances of overt violence and many are not obviously political. The rail thin, elderly black woman in a bright dress holding an umbrella striding purposefully past a clapboard wall in South Carolina is not the sort of subject that incites righteous indignation. Is there racial tension between the two women sitting next to each other at a New York lunch counter in 1962, one black with pearls in her hair, the other white wearing pearls around her neck? Maybe, maybe not.